There’s an open secret in America: If you want to kill someone, do it with a car. As long as you’re sober, chances are you’ll never be charged with any crime, much less manslaughter. Over the past hundred years, as automobiles have been woven into the fabric of our daily lives, our legal system has undermined public safety, and we’ve been collectively trained to think of these deaths as unavoidable “accidents” or acts of God. Today, despite the efforts of major public-health agencies and grassroots safety campaigns, few are aware that car crashes are the number one cause of death for Americans under 35. But it wasn’t always this way.

“At some point, we decided that somebody on a bike or on foot is not traffic, but an obstruction to traffic.”

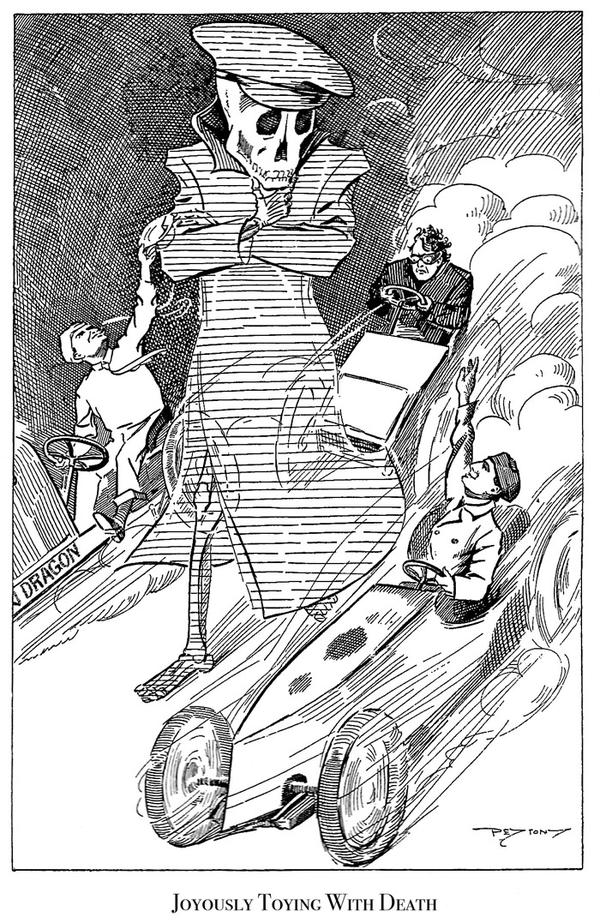

“If you look at newspapers from American cities in the 1910s and ’20s, you’ll find a lot of anger at cars and drivers, really an incredible amount,” says Peter Norton, the author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. “My impression is that you’d find more caricatures of the Grim Reaper driving a car over innocent children than you would images of Uncle Sam.”

Though various automobiles powered by steam, gas, and electricity were produced in the late 19th century, only a handful of these cars actually made it onto the roads due to high costs and unreliable technologies. That changed in 1908, when Ford’s famous Model T standardized manufacturing methods and allowed for true mass production, making the car affordable to those without extreme wealth. By 1915, the number of registered motor vehicles was in the millions.

Top: A photo of a fatal car wreck in Somerville, Massachusetts, in 1933. Via the Boston Public Library. Above: The New York Times coverage of car violence from November 23, 1924.

Within a decade, the number of car collisions and fatalities skyrocketed. In the first four years after World War I, more Americans died in auto accidents than had been killed during battle in Europe, but our legal system wasn’t catching on. The negative effects of this unprecedented shift in transportation were especially felt in urban areas, where road space was limited and pedestrian habits were powerfully ingrained.

For those of us who grew up with cars, it’s difficult to conceptualize American streets before automobiles were everywhere. “Imagine a busy corridor in an airport, or a crowded city park, where everybody’s moving around, and everybody’s got business to do,” says Norton. “Pedestrians favored the sidewalk because that was cleaner and you were less likely to have a vehicle bump against you, but pedestrians also went anywhere they wanted in the street, and there were no crosswalks and very few signs. It was a real free-for-all.”

A typical busy street scene on Sixth Avenue in New York City shows how pedestrians ruled the roadways before automobiles arrived, circa 1903. Via Shorpy.

Roads were seen as a public space, which all citizens had an equal right to, even children at play. “Common law tended to pin responsibility on the person operating the heavier or more dangerous vehicle,” says Norton, “so there was a bias in favor of the pedestrian.” Since people on foot ruled the road, collisions weren’t a major issue: Streetcars and horse-drawn carriages yielded right of way to pedestrians and slowed to a human pace. The fastest traffic went around 10 to 12 miles per hour, and few vehicles even had the capacity to reach higher speeds.

“The real battle is for people’s minds, and this mental model of what a street is for.”

In rural areas, the car was generally welcomed as an antidote to extreme isolation, but in cities with dense neighborhoods and many alternate methods of transit, most viewed private vehicles as an unnecessary luxury. “The most popular term of derision for a motorist was a ‘joyrider,’ and that was originally directed at chauffeurs,” says Norton. “Most of the earliest cars had professional drivers who would drop their passengers somewhere, and were expected to pick them up again later. But in the meantime, they could drive around, and they got this reputation for speeding around wildly, so they were called joyriders.”

Eventually, the term spread to all types of automobile drivers, along with pejoratives like “vampire driver” or “death driver.” Political cartoons featured violent imagery of so-called “speed demons” murdering innocents as they plowed through city streets in their uncontrollable vehicles. Other editorials accused drivers of being afflicted with “motor madness” or “motor rabies,” which implied an addiction to speed at the expense of human life.

This cartoon from 1909 shows the outrage felt by many Americans that wealthy motorists could hurt others without consequence. Via the Library of Congress.

In an effort to keep traffic flowing and solve legal disputes, New York City became the first municipality in America to adopt an official traffic code in 1903, when most roadways had no signage or traffic controls whatsoever. Speed limits were gradually adopted in urban areas across the country, typically with a maximum of 10 mph that dropped to 8 mph at intersections.

By the 1910s, many cities were working to improve their most dangerous crossings. One of the first tactics was regulating left-turns, which was usually accomplished by installing a solid column or “silent policeman” at the center of busy intersections that forced vehicles to navigate around it. Cars had to pass this mid-point before turning left, preventing them from cutting corners and speeding recklessly into oncoming traffic.

Left, a patent for a Silent Policeman traffic post, and right, an ad for the Cutter Company’s lighted post, both from 1918.

A variety of innovative street signals and markings were developed by other cities hoping to tame the automobile. Because they were regularly plowed over by cars, silent policemen were often replaced by domed, street-level lights called “traffic turtles” or “traffic mushrooms,” a style popularized in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Detroit reconfigured a tennis court line-marker as a street-striping device for dividing lanes. In 1914, Cleveland installed the first alternating traffic lights, which were manually operated by a police officer stationed at the intersection. Yet these innovations did little to protect pedestrians.

“What evil bastard would drive their speeding car where a kid might be playing?”

By the end of the 1920s, more than 200,000 Americans had been killed by automobiles. Most of these fatalities were pedestrians in cities, and the majority of these were children. “If a kid is hit in a street in 2014, I think our first reaction would be to ask, ‘What parent is so neglectful that they let their child play in the street?,’” says Norton.

“In 1914, it was pretty much the opposite. It was more like, ‘What evil bastard would drive their speeding car where a kid might be playing?’ That tells us how much our outlook on the public street has changed—blaming the driver was really automatic then. It didn’t help if they said something like, ‘The kid darted out into the street!,’ because the answer would’ve been, ‘That’s what kids do. By choosing to operate this dangerous machine, it’s your job to watch out for others.’ It would be like if you drove a motorcycle in a hallway today and hit somebody—you couldn’t say, ‘Oh, well, they just jumped out in front of me,’ because the response would be that you shouldn’t operate a motorcycle in a hallway.”

Left, an ad for the Milwaukee-style traffic mushroom, and right, the device in action on Milwaukee streets, circa 1926. Via the Milwaukee Public Library.

In the face of this traffic fatality epidemic, there was a fierce public outcry including enormous rallies, public memorials, vehement newspaper editorials, and even a few angry mobs that attacked motorists following a collision. “Several cities installed public memorials to the children hit by cars that looked like war monuments, except that they were temporary,” says Norton. “To me, that says a lot, because you collectively memorialize people who are considered a public loss. Soldiers killed in battle are mourned by the whole community, and they were doing that for children killed in traffic, which really captures how much the street was considered a public space. People killed in it were losses to the whole community.”

As the negative press increased and cities called for lower speed limits and stricter enforcement, the burgeoning auto industry recognized a mounting public-relations disaster. The breaking point came in 1923, when 42,000 citizens of Cincinnati signed a petition for a referendum requiring any driver in the city limits to have a speed governor, a mechanical device that would inhibit the fuel supply or accelerator, to keep vehicles below 25 miles per hour. (Studies show that around five percent of pedestrians are killed when hit by vehicles traveling under 20 miles per hour, versus 80 percent for cars going 40 miles an hour or more.)

The Cincinnati referendum logically equated high vehicle speeds with increasing danger, a direct affront to the automobile industry. “Think about that for a second,” Norton says. “If you’re in the business of selling cars, and the public recognizes that anything fast is dangerous, then you’ve just lost your number-one selling point, which is that they’re faster than anything else. It’s amazing how completely the auto industry joined forces and mobilized against it.”

One auto-industry response to the Cincinnati referendum of 1923 was to conflate speed governors with negative stereotypes about China. Via the Cincinnati Post.

“Motordom,” as the collective of special interests including oil companies, auto makers, auto dealers, and auto clubs dubbed itself, launched a multi-pronged campaign to make city streets more welcoming to drivers, though not necessarily safer. Through a series of social, legal, and physical transformations, these groups reframed arguments about vehicle safety by placing blame on reckless drivers and careless pedestrians, rather than the mere presence of cars.

In 1924, recognizing the crisis on America’s streets, Herbert Hoover launched the National Conference on Street and Highway Safety from his position as Commerce Secretary (he would become President in 1929). Any organizations interested or invested in transportation planning were invited to discuss street safety and help establish standardized traffic regulations that could be implemented across the country. Since the conference’s biggest players all represented the auto industry, the group’s recommendations prioritized private motor vehicles over all other transit modes.

A woman poses with a newly installed stop sign in Los Angeles in 1925, built to the specifications recommended at the first National Conference on Street Safety. Via USC Libraries.

Norton suggests that the most important outcome of this meeting was a model municipal traffic ordinance, which was released in 1927 and provided a framework for cities writing their own street regulations. This model ordinance was the first to officially deprive pedestrians access to public streets. “Pedestrians could cross at crosswalks. They could also cross when traffic permitted, or in other words, when there was no traffic,” explains Norton. “But other than that, the streets were now for cars. That model was presented to the cities of America by the U.S. Department of Commerce, which gave it the stamp of official government recommendation, and it was very successful and widely adopted.” By the 1930s, this legislation represented the new rule of the road, making it more difficult to take legal recourse against drivers.

Meanwhile, the auto industry continued to improve its public image by encouraging licensing to give drivers legitimacy, even though most early licenses required no testing. Norton explains that in addition to the revenue it generated, the driver’s license “would exonerate the average motorist in the public eye, so that driving itself wouldn’t be considered dangerous, and you could direct blame at the reckless minority.” Working with local police and civic groups like the Boy Scouts, auto clubs pushed to socialize new pedestrian behavior, often by shaming or ostracizing people who entered the street on foot. Part of this effort was the adoption of the term “jaywalker,” which originally referred to a clueless person unaccustomed to busy city life (“jay” was slang for a hayseed or country bumpkin).

Left, a cartoon from 1923 mocks jaywalking behavior. Via the National Safety Council. Right, a 1937 WPA poster emphasizes jaywalking dangers.

“Drivers first used the word ‘jaywalker’ to criticize pedestrians,” says Norton, “and eventually, it became an organized campaign by auto dealers and auto clubs to change attitudes about walking in the street wherever you wanted to. They had people dressed up like idiots with sandwich board signs that said ‘jaywalker’ or men wearing women’s dresses pretending to be jaywalkers. They even had a parade where a clown was hit by a Model T over and over again in front of the crowd. Of course, the message was that you’re stupid if you walk in the street.” Eventually, cities began adopting laws against jaywalking of their own accord.

In 1928, the American Automobile Association (AAA) took charge of safety education for children by sending free curricula to every public school in America. “Children would illustrate posters with slogans like, ‘Why I should not play in the street’ or ‘Why the street is for cars’ and so on,” explains Norton. “They took over the school safety patrols at the same time. The original patrols would go out and stop traffic for other kids to cross the street. But when AAA took over, they had kids sign pledges that said, ‘I will not cross the street except at the intersection,’ and so on. So a whole generation of kids grew up being trained that the streets were for cars only.” Other organizations like the Automobile Safety Foundation and the National Safety Council also helped to educate the public on the dangers of cars, but mostly focused on changing pedestrian habits or extreme driver behaviors, like drunk driving.

Street-safety posters produced by AAA in the late 1950s focused on changing behavior of children, rather than drivers.

Once the social acceptance of private cars was ensured, automobile proponents could begin rebuilding the urban environment to accommodate cars better than other transit modes. In the 1920s, America’s extensive network of urban railways was heavily regulated, often with specific fare and route restrictions as well as requirements to serve less-profitable areas. As motor vehicles began invading streetcar routes, these companies pushed for equal oversight of private cars.

“Automobiles could drive on the tracks,” explains Norton, “so this meant that as soon as just five percent of the people in cities were going around by car, they slowed the street railways down significantly, and streetcars couldn’t make their schedules anymore. They could ring a bell and try to make drivers get off their tracks, but if the driver couldn’t move because of other traffic, they were stuck. So the streetcars would just stand in traffic like automobiles.”

GE streetcar ads from 1928, left, and the early 1940s, right, emphasize the efficiency of mass transit over private automobiles.

The final blow was delivered in 1935 with the Public Utility Holding Company Act, which forced electric-utility companies to divest their streetcar businesses. Though intended to reduce corruption and regulate these growing electric utilities, this law removed the subsidies supporting many streetcar companies, and as a result, more than 100 transit companies failed over the next decade.

Even as government assistance was removed from these mass-transit systems, the growing network of city streets and highways was receiving ever more federal funding. Many struggling metro railways were purchased by a front company (operated by General Motors, Firestone Rubber, Standard Oil, and Phillips Petroleum), that ripped up their tracks to make way for fleets of buses, furthering America’s dependency on motor vehicles.

Meanwhile, traffic engineers were reworking city streets to better accommodate motor vehicles, even as they recognized cars as the least equitable and least efficient form of transportation, since automobiles were only available to the wealthy and took up 10 times the space of a transit rider. Beginning in Chicago, traffic engineers coordinated street signals to keep motor vehicles moving smoothly, while making crossing times unfriendly to pedestrians.

An aerial view from 1939 of 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, in Washington, D.C., shows early street markings. Via shorpy.com.

“Long after its victory, Motordom fought to keep control of traffic problems. Its highway engineers defined a good thoroughfare as a road with a high capacity for motor vehicles; they did not count the number of persons moved,” Norton writes in Fighting Traffic. Today our cities still reflect this: The Level of Service (LOS) measurement by which most planners use to gauge intersection efficiency is based only on motor-vehicle delays, rather than the impact to all modes of transit.

As in other American industries ranging from health care to education, those with the ability to pay for the best treatment were prioritized over all others. One 1941 traffic-control textbook read: “If people prefer to drive downtown and can afford it, then facilities must be built for them up to their ability to pay. The choice of mode of travel is their own; they cannot be forced to change on the strength of arguments of efficiency or economy.”

All the while, traffic violence continued unabated, with fatalities increasing every year. The exception was during World War II, when fuel shortages and resource conservation led to less driving, hence a drop in the motor-vehicle death rates, which spiked again following the war’s conclusion. By the time the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act was passed in 1956, the U.S. was fully dependent on personal automobiles, favoring the flexibility of cars over the ability of mass transit to carry more people with less energy in a safer manner.

In 1962, Boston formally adopted jaywalking laws to penalize pedestrians.

In 1966, Ralph Nader published his best-selling book, Unsafe At Any Speed, which detailed the auto industry’s efforts to suppress safety improvements in favor of profits. In the preface to his book, Nader pointed out the huge costs inflicted by private vehicle collisions, noting that “…these are not the kind of costs which fall on the builders of motor vehicles (excepting a few successful lawsuits for negligent construction of the vehicle) and thus do not pinch the proper foot. Instead, the costs fall to users of vehicles, who are in no position to dictate safer automobile designs.” Instead of directing money at prevention, like vehicle improvements, changing behaviors, and road design, money is spent on treating the symptoms of road violence. Today, the costs of fatal crashes are estimated at over $99 billion in the U.S., or around $500 for every licensed driver, according to the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

Nader suggested that the protection of our “body rights,” or physical safety, needed the same broad support given to civil rights, even in the face of an industry with so much financial power. “A great problem of contemporary life is how to control the power of economic interests which ignore the harmful effects of their applied science and technology. The automobile tragedy is one of the most serious of these man-made assaults on the human body,” Nader wrote.

Dr. David Sleet, who works in the Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention at the CDC, says Nader’s book was a game-changer. “That really started this whole wave of improvements in our highway-safety problem,” says Sleet. “The death rates from vehicle crashes per population just kept steadily increasing from the 1920s until 1966. Two acts of Congress were implemented in 1966, which initiated a national commitment to reducing injuries on the road by creating agencies within the U.S. Department of Transportation to set standards and regulate vehicles and highways. After that, the fatalities started to decline.”

Ralph Nader’s book, “Unsafe at Any Speed,” brought a larger awareness to America’s traffic fatalities, and targeted design issues with the Corvair. A few years prior, in 1962, comedian Ernie Kovacs was killed in a Corvair wagon, seen at right wrapped around a telephone pole.

The same year Nader’s book was published, President Lyndon Johnson signed the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act and the Highway Safety Act. This legislation led to the creation of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), which set new safety standards for cars and highways. A full 50 years after automobiles had overtaken city streets, federal agencies finally began addressing the violence as a large-scale, public-health issue. In 1969, NHTSA director Dr. William Haddon, a public-health physician and epidemiologist, recognized that like infectious diseases, motor-vehicle deaths were the result of interactions between a host (person), an agent (motor vehicle), and their environment (roadways). As directed by Haddon, the NHTSA enforced changes to features like seat belts, brakes, and windshields that helped improve the country’s fatality rate.

Following the release of Nader’s book, grassroots organizations like Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD, 1980) formed to combat car-safety issues that national legislators were not addressing. The CDC began adapting its public-health framework to the issue of motor-vehicle injury prevention in 1985, focusing on high-risk populations like alcohol-impaired drivers, motorcyclists, and teenagers.

In the late 1970s, the NHTSA standardized crash tests, like this 90 mph test of two Volvos.

“I think the perennial problem for us, as a culture, is recognizing that these injuries are both predictable and preventable,” says Sleet. “The public still has not come around to thinking of motor-vehicle crashes as something other than ‘accidents.’ And as long as you believe they’re accidents or acts of fate, then you won’t do anything to prevent them. The CDC continues to stress that motor-vehicle injuries, like diseases, are preventable.”

Sleet says the CDC’s approach is similar to its efforts against smoking: The first step is understanding the magnitude of the problem or threat, the second is identifying risk factors, and the third is developing interventions that can reduce these factors. “The last stage is getting widespread adoption of these known and effective interventions,” explains Sleet. “The reason we think motor-vehicle injuries represent a winnable battle is that there are lots of effective interventions that are just not used by the general public. We’ve been fighting this battle of increasing injuries since cars were first introduced into society, and we still haven’t solved it.

“Public health is a marathon, not a sprint,” adds Sleet. “It’s taken us 50 years since the first surgeon general’s report on smoking to make significant progress against tobacco. We need to stay the course with vehicle injuries.”

Though their advocacy is limited to drunk driving, MADD is one of the few organizations to use violent imagery to promote road safety, as seen in this ad from 2007.

Although organizations like the CDC have applied this public-health approach to the issue for decades now, automobiles remain a huge danger. While the annual fatality rate has dropped significantly from its 1930s high at around 30 deaths for every 100,000 persons to 11 per 100,000 in recent years, car crashes are still a top killer of all Americans. For young people, motor-vehicle collisions remain the most common cause of death. In contrast, traffic fatalities in countries like the United Kingdom, where drivers are presumed to be liable in car crashes, are about a third of U.S. rates.

In 2012, automobile collisions killed more than 34,000 Americans, but unlike our response to foreign wars, the AIDS crisis, or terrorist attacks—all of which inflict fewer fatalities than cars—there’s no widespread public protest or giant memorial to the dead. We fret about drugs and gun safety, but don’t teach children to treat cars as the loaded weapons they are.

“These losses have been privatized, but in the ’20s, they were regarded as public losses,” says Norton. After the auto industry successfully altered street norms in the 1920s, most state Departments of Transportation actually made it illegal to leave roadside markers where a loved one was killed. “In recent years, thanks to some hard work by grieving families, the rules have changed in certain states, and informal markers are now allowed,” Norton adds. “Some places are actually putting in DOT-made memorial signs with the names of victims. The era of not admitting what’s going on is not quite over, but the culture is changing.”

In recent years, white Ghost Bikes have been installed on roadways across the country where cyclists were killed by motorists, like this bike in Boulder, Colorado, in memory of Matthew Powell.

“Until recently, there wasn’t any kind of concerted public message around the basic danger of driving,” says Ben Fried, editor of the New York branch of Streetsblog, a national network of journalists chronicling transportation issues. “Today’s street safety advocates look to MADD and other groups that changed social attitudes toward drunk driving in the late ’70s and early ’80s as an example of how to affect these broad views on how we drive. Before you had those organizations advocating for victims’ families, you would hear the same excuses for drunk driving that you hear today for reckless driving.”

Though drunk driving has long been recognized as dangerous, seen in this WPA poster from 1937, reckless driving has been absent from most safety campaigns.

Though anti-drunk-driving campaigns are familiar to Americans, fatalities involving alcohol only account for around a third of all collisions, while the rest are caused by ordinary human error. Studies also show that reckless drivers who are sober are rarely cited by police, even when they are clearly at fault. In New York City during the last five years, less than one percent of drivers who killed or injured pedestrians and cyclists were ticketed for careless driving. (In most states, “negligent” driving, which includes drunk driving, has different legal consequences than “reckless” driving, though the jargon makes little difference to those hurt by such drivers.)

Increasingly, victims and their loved ones are making the case that careless driving is as reprehensible as drunk driving, advocating a cultural shift that many drivers are reluctant to embrace. As with auto-safety campaigns in the past, this grassroots effort is pushing cities to adopt legislation that protects against reckless drivers, including laws inspired by Sweden’s Vision Zero campaign. First implemented in 1997, Vision Zero is an effort to end all pedestrian fatalities and serious injuries; recently, cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco also announced their goals of eliminating traffic deaths within 10 years. Other initiatives are being introduced at the state level, including “vulnerable user laws,” which pin greater responsibility on road users who wield the most power whether a car compared to a bicyclist, or a biker to a pedestrian.

Fried says that most people are aware of the dangers behind the wheel, but are accustomed to sharing these risks, rather than taking individual responsibility for careless behavior. “So many of us drive and have had the experience of not following the law to a T—going a little bit over the speed limit or rolling through a stop sign,” he explains. “So there’s this tendency to deflect our own culpability, and that’s been institutionalized by things like no-fault laws and car insurance, where we all share the cost for the fact that driving is a dangerous thing.”

This dark political cartoon from “Puck” magazine in 1907 suggested that speeding motorists were chasing death. Via the Library of Congress.

As cities attempt to undo years of car-oriented development by rebuilding streets that better incorporate public transit, bicycle facilities, and pedestrian needs, the existing bias towards automobiles is making the fight to transform streets just as intense as when cars first arrived in the urban landscape. “The fact that changes like redesigning streets for bike lanes set off such strong reactions today is a great analogy to what was going on in the ’20s,” says Fried. “There’s a huge status-quo bias that’s inherent in human nature. While I think the changes today are much more beneficial than what was done 80 years ago, the fact that they’re jarring to people comes from the same place. People are very comfortable with things the way they are.”

However, studies increasingly show that most young people prefer to live in dense, walkable neighborhoods, and are more attuned to the environmental consequences of their transportation than previous generations. Yet in the face of clear evidence that private automobiles are damaging to our health and our environment, most older Americans still cling to their cars. Part of this impulse may be a natural resistance to change, but it’s also reinforced when aging drivers have few viable transportation alternatives, particularly in suburban areas or sprawling cities with terrible public transit.

“People don’t have to smoke,” Sleet says, “whereas people might feel they do need a car to get to work. Our job is to try and make every drive a safe drive. I think we can also reduce the dependency we have on motor vehicles, but that’s not going to happen until we provide other alternatives for people to get from here to there.”

Gory depictions of car violence became rare in the United States after the 1920s, though they persisted in Europe, as seen in his German safety poster from 1930 that reads, “Motorist! Be Careful!” Via the Library of Congress.

Fried says that unlike campaigns for smoking and HIV reduction, American cities aren’t directly pushing people to change their behavior. “You don’t see cities saying outright that driving is bad, or asking people to take transit or ride a bike, in part because they’re getting flack from drivers. No one wants to be seen as ‘anti-car,’ so their message has mostly been about designing streets for greater safety. I think, by and large, this has been a good choice.”

“The biggest reductions in traffic injuries that the New York City DOT has been able to achieve are all due to reallocating space from motor vehicles to pedestrians and bikes,” says Fried. “The protected bike-lane redesigns in New York City are narrowing the right of way for vehicles by at least 8 feet, and sometimes more. If you’re a pedestrian, that’s 8 more feet that you don’t have to worry about when you’re crossing the street. And if you’re driving, the design gives you cues to take it a bit slower because the lanes are narrower. You’re more aware of how close you are to other moving objects, so the incidence of speeding isn’t as high as it used to be. All these changes contribute to a safer street environment.”

Like in the 1920s, these infrastructure changes really start with a new understanding of acceptable street behavior. “That battle for street access of the 1910s and ’20s, while there was a definite winner, it never really ended,” says Norton. “It’s a bit like the street became an occupied country, and you have a resistance movement. There have always been pedestrians who are like, ‘To hell with you, I’m crossing anyway.’

“The people who really get it today, in 2014, know that the battle isn’t to change rules or put in signs or paint things on the pavement,” Norton continues. “The real battle is for people’s minds, and this mental model of what a street is for. There’s a wonderful slogan used by some bicyclists that says, ‘We are traffic.’ It reveals the fact that at some point, we decided that somebody on a bike or on foot is not traffic, but an obstruction to traffic. And if you look around, you’ll see a hundred other ways in which that message gets across. That’s the main obstacle for people who imagine alternatives—and it’s very much something in the mind.”